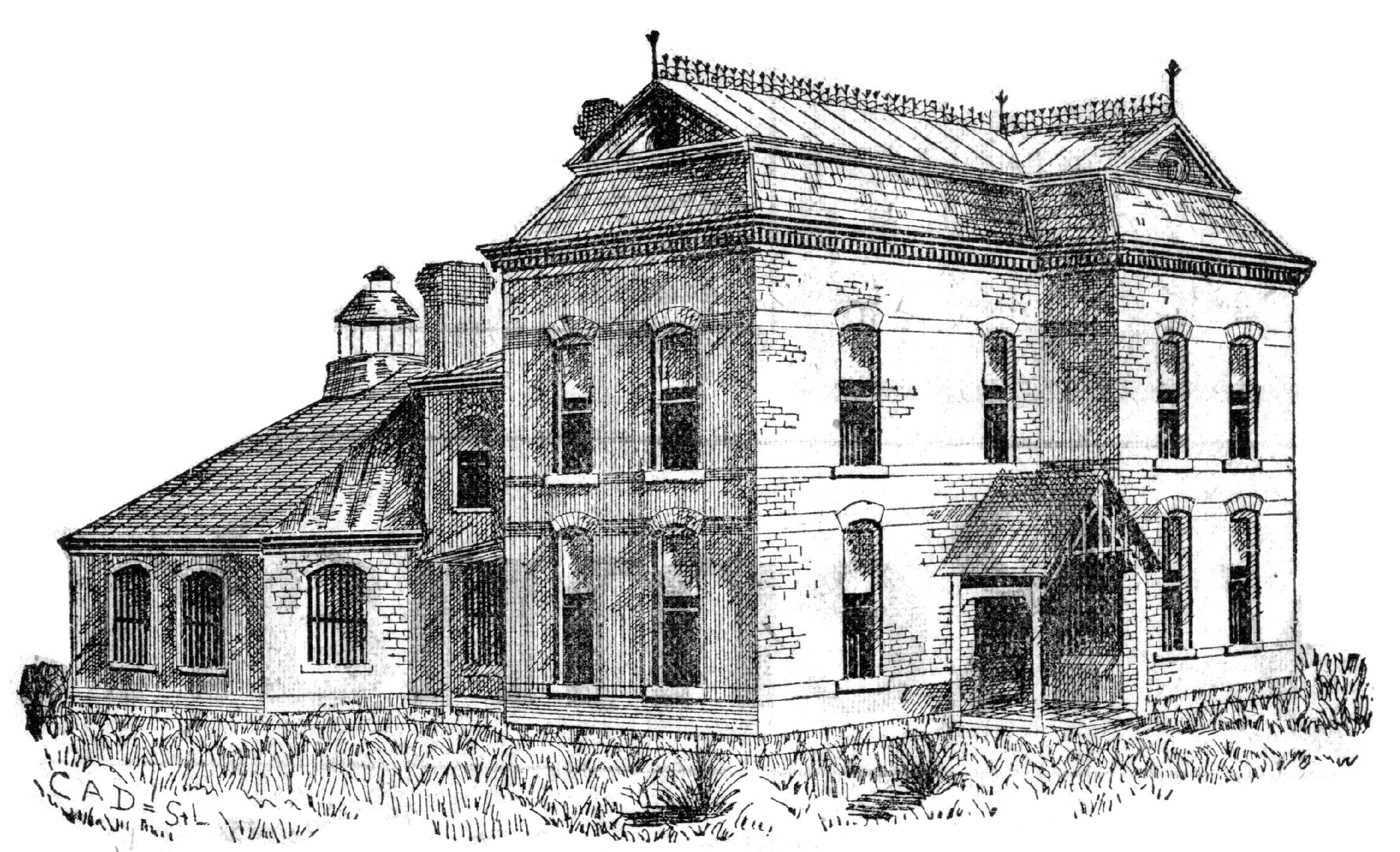

The “Slave Mansion” which once operated as a farm just outside of Kidder, MO. Teresa Eaton not only grew up nearby but her family has primary information revealing details and insights which have evolved into local lore.

Teresa says the man who built the “Slave Mansion” was P.S. Kenney, her great-great-great uncle. He was an Irish Catholic who came to America as a result of the potato famine in his native homeland.

Kenney was a prominent businessman and instrumental in luring the railroad into the area and, thus, founding Kidder. According to the State Historical Society of Missouri, the home of P.S. Kenney was briefly used as a railroad station. This was prior to 1860 while Kenney owned a store and presided over a post office called Emmett. The community’s name was changed to Kidder when a depot was established. Kinney also donated the land for the cemetery which bears his name, where his resting place is marked by an impressive 10-foot monument that can still be seen today. Local lore adds color to this cemetery with claims of mass burials of slaves and Chinese railroad workers supposedly located in a corner.

This grave marker in the Kidder Cemetery marks the resting place of Patrick S. Kenney, an Irish Catholic who came to America as a result of the potato famine in his native homeland.

What’s more, Teresa’s mother- and father-in-law, Virginia and Glenn Eaton, lived in the Kenney “Slave Mansion” when the couple married in the mid-1950s. Virginia tells Teresa how they seldom went down into the basement of the home, but Virginia recalls a cellar entrance had caved in and was still evident in the basement. It could be that this fueled local rumors about a slave tunnel which some say connected to a nearby barn.

What is known with more certainty can be seen at the Kidder City Park. The cupola, once perched atop the Kenney farmhouse, was relocated to the park. No doubt the cupola offered advantages to view the horizon on all directions when built atop the farmhouse during Civil War times, whether for farm management purposes or to lookout for Jayhawkers.

In 2018 the cupola was still to be seen in Kidder. It harkens back to local lore to those visiting the Kidder Park. Otherwise, nothing about the Slave Mansion exists. If you venture west of Kidder to where it once stood (about two miles on the county line, as if traveling by horse and buggy), you’ll only see a cornfield.

In 1971 Johnnie Black of Gallatin used his Kodak box camera while on a fifth grade field trip to take photos of a vacant farmhouse near Kidder. This was the “plantation” owned by Patrick Kenny, once profitable due to slave labor. Community lore described a tunnel between the home and barn, where slaves were hidden whenever Jayhawkers approached both preceding and during the Civil War. The cupola on the home was used as a lookout. These buildings no longer exist.

This building no longer exists.

This building no longer exists.

This building no longer exists.

MORE NOTES ON KIDDER:

The city was laid out in 1860 by Geo. S. Harris for F. W. Hunnewell and Ed. L. Baker, trustees of the Kidder Land Company of Boston and named for H.P. Kidder. The land company was seeking to encourage non-slave owning European immigrants to settle along the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad which at the time was the furthest west railroad in the United States. The town site was almost a mile square.

In its early days, Kidder was called the “Athens of Caldwell County” for its interests in scholarship. From its inception, a college was part of this community’s plans. Thayer College was founded in 1871 and closed in 1876. The campus was known as Thayer College and Thayer High School. It reopened in 1877 as the Kidder Institute and operated under the auspices of the Congregational Church of Missouri. The building was used as a public school from 1934 to 1981. The property eventually was purchased for private purposes.

In 2004 Kidder received national publicity after a student at the Thayer Learning Center, operating in these buildings, died after not receiving treatment early enough. In 2009 the Center was sold to become the White Buffalo Academy.