The following, in part, is written by Martin McGrane for the February 1980 edition of Rural Missouri. Photos shown here were added after this article’s initial publication.

Not many people become international celebrities without a little promotional help along the way — and Missouri’s famous bandit brothers, Frank and Jesse James, were no exceptions. And while it might be too generous to give John Edwards all the credit for history’s image of the James boys, he certainly deserves a healthy dose.

Edwards was a pioneer Missouri newspaperman, one of the most respected of his generation. But more than that, he was a public relations man operating during an era that hadn’t even coined the term. Using a hero-building formula that had been around for centuries, in tandem with PR techniques so innovative they wouldn’t have labels for another 70 years, he gave the James brothers an image so appealing that it prompted one of Missouri’s most famous skeptics, Harry Truman, to remark: “Jesse was a modern-day Robin Hood. He stole from the rich and gave to the poor, which, in general, is not a bad policy.”

Formerly of the Confederate Missouri Brigade, prominent newspaper publisher John Newman Edwards defended the James Boys to arouse public sympathies and also arranged for the surrend of Frank James.

Edwards was born in Front Royal, VA, in 1839. He came to Missouri in the mid-1850s, first working as a printer for the Lexington Expositor. When the Civil War began he joined the Confederate Army and won a major’s commission while serving as an adjutant to his friend, General Jo Shelby. Between the war’s end and the time of his death in 1889, Edwards wrote for at least six different Missouri newspapers, authored two books — and became a moody, introverted alcoholic.

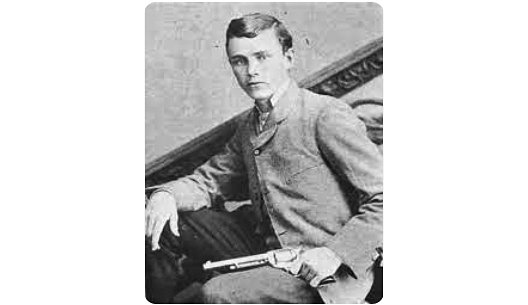

Charles Fletcher Taylor, left, is shown with brothers Frank and Jesse James. When the Civil War erupted, martial law was declared because of the state of unrest. As Jayhawkers from Kansas began to invade Missouri to burn, loot, and in many cases, shoot or hang the pro-Southern farmers, William Clarke Quantrill took charge of a 15-man posse formed to pursue Jayhawkers. Charles Fletcher Taylor was one of these men which developed into the notorious Quantrill’s Raiders.

Edwards probably met Frank and Jesse James when they were teenaged Confederate guerrillas riding with William Clarke Quantrill and “Bloody Bill” Anderson. The James boys went back to their mother’s farm near Kearney, MO, after the war and although they’ve often been accused of launching their careers with a hit on the Clay County Savings Bank in Liberty, MO, on Feb. 13, 1866, it wasn’t until two men robbed the Daviess County Savings Association at Gallatin on Dec. 7, 1869, that Frank and Jesse came under public suspicion.

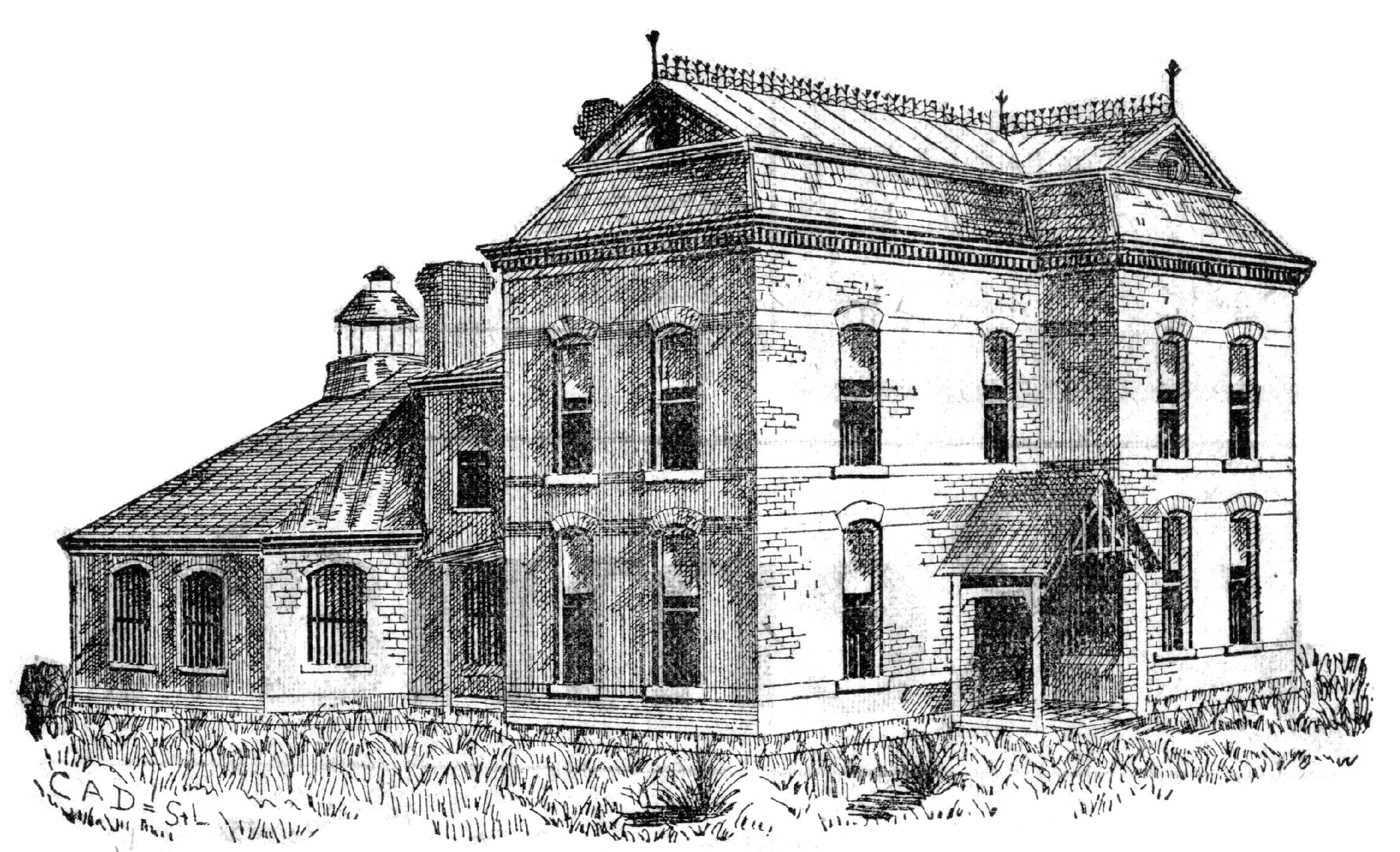

This is an artist’s concept of the 1869 fatal shooting of Capt. John Sheets of Gallatin, allegedly by Frank and Jesse James. Soon thereafter, the James brothers were declared wanted outlaws by the State of Missouri for the first time in their notorious reign of crime.

By 1872, Edwards was actively involved in glamorizing local crimes charged against unknown ex-guerrillas in general and the James brothers in particular. Perhaps fantasizing that some remnant of the Confederacy still rode whenever the old bushwhackers went outside the law, Edwards began to glorify them, not for the crimes they committed but for the way they did things. Two days after three armed men rode up to the cashier’s window at the Kansas City fairgrounds and came away with $978, while a crowd estimated at 10,000 gaped in astonishment, Edwards published an editorial in the Kansas City Times (which he helped organize in 1868) that showed his admiration for the flashy lawlessness of the ex-guerrillas:

“There are men …who learned to dare when there was no such word as quarter in the dictionary of the Border. Men who have carried their lives in their hands so long they do not know how to commit them over into the keeping of the laws an regulations that exist now, and these men sometimes rob. But it is always in the glare of the day and in the teeth of the multitude. With them booty is but the second thought; the wild drama of the adventure first …These men are bad citizens but they are bad because they live out of their time. The nineteenth century …is not the social soil for men who might have sat with Arthur at the Round Table, ridden at tourney with Sur Launcelot…

“What they did we condemn. But the way they did it we cannot help admiring… It was as though three bandits had come to us from the storied Odenwald, with the halo of medieval chivalry upon their garments…”

Other local editorial writers saw the fairgrounds robbery in a different light. Commenting that a young girl had been accidentally shot and seriously wounded during the fracas, the Kansas City Daily Journal of Commerce stated: “More audacious villains than the perpetrators of this robbery, or those more deserving of hanging on a limb do not exist at this moment.”

Whether he consciously realized it or not, Edwards’ defense of the James brothers and other ex-guerrillas had, by then, already begun to follow a formula for hero-making that had been used for centuries. In immortalizing England’s Robin Hod, Germany’s Schinderhannes, Italy’s Fra Diavalo and Australia’s Ned Kelly, writers have used a consistent, proven scenario. The young hero is forced into a life of crime; his crimes are noble and justifiable (he steals from the rich and gives to the poor); he is kind to defenseless women and children, but a scourge to evil men — and he is eventually killed by a wretched, honor-starved traitor.

Jesse James, shown as a teenager riding with Confederate guerrillas in 1864, is one of the best known photos of the man destined to be America’s No. 1 outlaw after the Civil War. He robbed banks, trains and stagecoaches and committed murders long after others accepted the defeat of the secessanists’ cause.

Edwards’ editorial that followed the Kansas City fairgrounds robbery hinted at this approach. And in 1877, when Frank and Jesse were already famous as bank and train robbers, Edwards published a 488-page book of real and imaged Civil War exploits called “Noted Guerrillas or the Warfare of the Border,” that plugged the James brothers into all but the last step of that historically proven formula. For openers, the book established the claim that Jesse was not allowed to return to peaceful postwar life by saying that he had been shot and seriously wounded while riding toward Lexington, MO, to surrender to federal troops after the war’s end. Then, in Chapter 18, Edwards eloquently described the kind of harassment he claimed drove Jesse to become a postwar outlaw:

“The hunt for this maimed and emaciated Guerrilla culminated on the night of Feb. 18, 1867. On this night an effort was made to kill him. Five militiamen, well armed and mounted, came to his mother’s house and demanded admittance. The weather was bitterly cold, and Jesse James, parched with a fever, was tossing wearily in bed. His pistols were under his head. His step-father, Dr. Samuel, heard the militiamen as they walked upon the front porch, and demanded to know what they wanted. They told him to open the door. He came up to Jess’s room and asked him what he should do. ‘Help me to the window,’ was the low, calm reply, ‘that I may look out.’ He did so. There was snow on the ground and the moon was shining. He saw that all the horses hitched to the fence had on cavalry saddles, and then he knew that the men were soldiers. He had be one of two things to do — drive them away or die…

He went down stairs softly, having first dressed himself, crept up close to the front door and listened until from the talk of the men he thought he was able to get a fatally accurate pistol range. Then he put a heavy dragoon revolver to within three inches of the upper panel of the door and fired. A man cried out and fell. Before the surprise was off he threw the door wide open, and with a pistol in each hand began a rapid fusillade. A second man was killed as he ran, two men were wounded severely, and surrendered, while the fifth marauder, terrified yet unhurt, rushed swiftly to his horse and escaped in the darkness.

“What else could Jesse James have done? He had been a desperate Guerrilla; he had fought under a black flag; he had made a name for terrible prowess along the border …hence the wanton war waged upon Jesse and Frank James, and hence the reason why today they are outlaws.”

But modern scholars haven’t found much to support Edwards’ claim that the James boys’ only postwar option was a life of crime. Dr. William A. Settle, Jr., author of a book called, “Jesse James Was His Name,” is one skeptic.

“How hostile was the environment in Missouri to which the wartime guerrillas, or even Confederate soldiers, returned in 1865 and later? In most communities, it was as hostile as the men themselves made it… ”

“For over four years after the end of the war the James boys lived at their mother’s home and came and went as they pleased. They apparently cultivated the farm when they were there and got along with their neighbors without serious difficulty in spite of their participation in the most immediate violence of the war in Missouri. During this time Jesse joined the Baptist Church in Kearney and was baptized. Had he and Frank never become involved in postwar banditry, they could, without any question, have lived peaceably at home. Examples are numerous of former Quantrill men who lived in peace and prospered quietly after the war.”

~~~

But Edwards did much more than just plug the James brothers’ exploits into a proven image-building formula. Over a span of years, letters attributed to Jesse kept popping up in whatever newspaper Edwards happened to be working for. That might have been coincidence, but the writing style shown in most of the letters was a stylistic dead-ringer for Edwards’ own flowery rhetoric. One of the earliest of them, printed in the Kansas City Times after a Gallatin, MO, robbery and shoot-out that left townspeople dead, was typical:

“I will never surrender to be mobbed by a set of bloodthirsty poltroons. It is true that during the war I was a Confederate soldier, fought under the black flag, but since then I have lived a peaceable citizen, and obeyed the laws of the United States to the best of my knowledge.”

The rival Kansas City Journal observed this flow of correspondence and said that the letters were becoming “suspiciously — almost nauseatingly — monotonous.” One letter that may actually have been Jesse’s work appeared in the Nashville, TN, Banner shortly after Pinkerton Agency detectives tossed either a bomb or a flare into his mother’s home in 1875, killing Jesse’s half brother Archie Peyton Samuel and mangling his mother’s arm so badly it had to be amputated later that same day. The tone of the letter printed in the Tennessee paper was chilling: “Justice is slow but sure, and they (sic) is a just God that will bring all to justice. Pinkerton, I hope and pray that our Heavenly Father may deliver you into my hands… ”

This is the farm home of the James family, where Frank & Jesse James grew up east of Kearney, MO, and later a place of refuge as the boys became wanted outlaws. Today the James Farm is a historic site and museum maintained by Clay County.

It seems likely that Edwards may have encouraged Jesse and Frank’s mother, Zerelda Samuel, to make herself available to the press to further her sons’ defenses. During one of those early-day press conferences, which followed a stagecoach robbery near Lexington that had been blamed on her sons, she insisted they were innocent and that all their troubles were due, just as Edwards had been saying, to the fact that they hadn’t been allowed to return to a peaceful postwar life. She made another public denial of the boys’ guilt after a Missouri Pacific train was robbed near Otterville in the summer of 1876, and again after a Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific train was hit near Winston, MO, in 1881. She said Frank and Jesse couldn’t have been involved in the Winston holdup, which took the lives of the train’s conductor and one passenger, because her sons were dead.

It was a nice try, but it wasn’t true.

One of the scenes painted by Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975) featured in the Missouri State Capitol at Jefferson City features outlaw Jesse James in a mythical train/bank robbery. Benton’s work adorns the House Lounge on the third floor of the Capitol. The murals were commissioned by the legislature in early 1935 for $16,000 and completed in December 1936.

After Bob Ford added the last element of the hero-building formula by killing Jesse on April 3, 1882, Edwards was quick to editorially point out that the men responsible were “self confessed robbers, highwaymen and prostitutes.” As with any true hero, Jesse had been killed by a wretch unworthy to stand in his presence.

Bobby Ford assassinated outlaw gang leader Jesse James (who often used Mr. Howard as an alias) to claim a $10,000 reward and, consequently, endured everlasting infamy for shooting James in the back.

With Jesse gone, Edwards turned his public relations strategies toward Frank’s defense. Though many people thought Frank would try to avenge his brother’s killing, Edwards knew better. Frank was ready to retire. On Aug. 1, 1882, Edwards wrote to him and the letter showed the kind of behind-the-scenes maneuvering he was involved in:

“I am now returned home from the Indian Territory (a term Settle says Edwards sued to indicate he was sober again, following a spree) to find your letters. Do not make a move until you hear from me again. I have been to the Governor (Thomas T. Crittenden) myself, and things are working. Lie quiet and make no stir… ”

Edwards went along when Frank surrendered to Crittenden on Oct. 4, 1882. The two of them turned the surrender into something of a media event, which wasn’t very surprising. Edwards, on entering the governor’s office, said, “Governor, I want to introduce you to my old friend Frank James.” Sensing the drama of the moment, Frank removed his pistol belt and told Crittenden, “I want to hand over to you that which no living man except myself has been permitted to touch since 1861, and to say that I am your prisoner.”

But even before Frank’s well-publicized surrender, Edwards had been pulling strings. He’d arranged for Charles P. Johnson, a former Missouri lieutenant governor, to head Frank’s large and capable defense team. Newspapers from around the country were jammed with coverage of Frank’s trial. He was charged with murdering one man during the 1869 Gallatin bank robbery and two more during the 1881 Winston train job. After an eloquent defense, Frank was acquitted and there’s no doubt that Edwards’ efforts at building a climate of public sympathy and support helped enormously. But there were more charges in the works and he wrote to Frank that he was still on the job:

“My Dear Frank:

I need not tell you how great a joy was the verdict… I am now quietly watching the expressions of public opinion and building up some breastworks. Never mind what the newspapers say, the masses are for you. The backbone of the prosecution has been broken. I have been through hell myself since I saw you, but I have driven out the pirates, and got the vessel again. Write to me. You friend, as ever,

J.N. Edwards”

Edwards kept on with his lobbying after John S. Marmaduke became Missouri governor in 1884. In a letter to Frank written in March, 1885, Edwards assured him that the new governor would never surrender him to Minnesota authorities to face charges stemming from the bungled Northfield raid that had sent Cole, Bob and Jim Younger to prison almost 10 years earlier.

“I have just five minutes ago left Governor Marmaduke,” Edwards wrote, “after a long, full, and perfect interview… I tell you that you are a free man, and can never be touched while Marmaduke is governor.”

That visit with the governor was Edwards’ last public relations gesture on behalf of Frank James. But even at the time of his death four years later, Edwards was still working for the men who had fought for the Confederacy — he was preparing a petition asking the release of the Youngers from their Minnesota prison.

~~~

Although Edwards was only one among hundreds of writers who published books, pamphlets and stories about the James brothers both during and after their lifetimes, he was different from the rest of the herd. For one thing, his was the original work. Much of what Edwards wrote about Frank, Jesse and the rest of the guerrillas was fiction, but it made fine reading and it was copied by hordes of his followers. Then too, Edward never wrote a word in defense of the James boys because he was after money or fame. A letter to Frank shortly after he was cleared of the Gallatin charges made that clear: “Whatever I do at ay time or upon any occasion is done with an eye simple to your interests. As for myself, I do not care one tinkers damn what is said, I shall stay to the end.”

In a review of Missouri’s first hundred years of journalism, written in 1920, Edwards won warm, understanding praise. He was, it said, “better known and better loved by his generation than any other newspaperman in any generation of the century… Out of the maze of romance his genius substituted for realities, his eloquence expressed itself in dreams… And what he could not otherwise endure, he idealized.”

General Jo Shelby with Major John Newman Edwards, his longtime adjutant during the war and lifetime friend

Edward never waivered in his loyalty to Missouri’s Confederates and he waged a long, self-consuming war to win acceptance for Frank and Jesse James. From time to time, Jesse showed some measure of gratitude. He named his son Jesse Edwards James. Frank, too, must have felt grateful for all the work Edwards did for him.

In a curious way, Edwards was using the James brothers. Through them the Union-flaunting Confederacy still lived and through daring, chivalrous raids — which had most of their reality in Edwards’ mind — dashing rebel guerrillas still outrode, outshot and outwitted their clumsy Union enemies. But if Edwards used the James brothers, they took advantage of his attention, too. Jesse liked the celebrity status that Edwards’ publicity gave him and a reported chance encounter with the famous author made that clear:

“Some time ago I was making a purchase in a small town store in Missouri. A man walked in and seeing me, came over with outstretched hand and said, ‘You’re Mark Twain, ain’t you!’ I nodded. ‘Guess yo and I are about the greatest in our lines’ to which I couldn’t help but nod but wonder as to what his throne of greatness he held. So I asked, ‘What’s your name?’ He replied, ‘Jesse James’ as he gathered up his packages.

So it seems that in the final measure, Edwards and the James brothers did rather well by one another. Edwards found the characters to flesh out a drama he’d probably been planning since the fall of the Confederacy. And the James boys, in turn, discovered a publicist with the skill to turn the bloody reality of their postwar livelihoods into something far more appealing. So appealing, in fact, that it’s become one of the best-loved legends in American history.